I thought with all the social turmoil the country is going through today that this story may be appropriate.

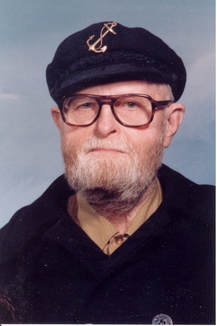

Papa was the best educated man I ever met. He finished high school in Texas but, as a poor farm boy, couldn’t afford to go to college.

There was no topic that didn’t interest Papa. He read everything he could get his hands on, from history to literature to poetry. He had vast amounts of Shakespeare, the Bible and poetry committed to memory. On any given day, you could count on him to quote Robert Browning, Shakespeare or John Masefield to you.

Papa’s sharp intelligence and vast span of knowledge served him well with the intellectual crowd. The university professors loved to come in for lunch and debate Papa about the issues of the day or the collapse of the Roman Empire. University students found Papa a willing resource. They came in and talked to him about their assignments and he told them where to look for books and documents to research.

Papa was also wildly radical in his politics. In the Thirties, he was a union organizer in San Francisco for the Longshoreman’s Union. As he worked on union activities he was exposed to the American Communist Party. Like millions of Americans during that time, he was greatly disillusioned with our system that appeared to be collapsing. The Soviet Union marketed themselves to be a “workers’ paradise” and Papa was always the champion for the working man.

A couple of weeks before we opened the El Sombrero, congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. It was an earthshaking event that went largely unnoticed in sleepy Oregon.

Within a few years, the war in Viet Nam escalated. We had over half a million troops in the country and disillusionment in the war was spreading at home. Eugene and the University of Oregon were on the cutting edge of the Peace Movement.

The U of O has always been a liberal school, but during the Sixties, Eugene became home to a large hippy population. It remains one of the last bastions of hippydom in the country.

El Sombrero became a hang out for the anti-war crowd. Every afternoon, after the lunch crowd dissipated, students, teachers and hippies gathered around tables in our restaurant plotting new demonstrations to show The Establishment that they could not continue to ignore the voice of the people. It was an exciting time and most young people on campus were involved in either pro or anti-government demonstrations.

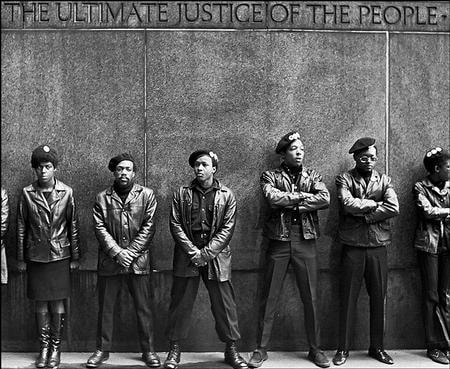

During the height of the debate, the U of O invited Huey Newton, the founder of the Black Panthers, to speak.

Early one morning Papa was setting up when a group of young black men, dressed in black jeans, T-shirts, leather jackets and berets entered the restaurant. He immediately recognized Huey. Papa grabbed a couple of menus and ran out to greet them.

“Good morning!”

“Hey, Whitey, what you got to eat here? You got any soul food?” Huey said in a loud voice full of disdain.

“No, this is a Mexican restaurant. I can fix you a great Mexican dinner.”

“Hey, Whitey, you own this place?

“Yes.”

“So you’re exploitin’ these poor workers. Just like you exploited my people for three hundred years. Just like you made us cotton slaves.”

Papa snapped. “Have you ever been a cotton slave?” he roared at Huey.

“No.”

“Well I have! I know what its like to hoe the cotton from sun up to sun down. I know what it’s like dragging a hundred-pound bag of cotton down row after row in the hundred-degree heat. Don’t you ever dare talk to me about being a cotton slave.”

Huey backed down, ordered breakfast and quietly left.

The world was in turmoil. It was 1968 and the presidential election was in full swing. Hubert Humphrey made an appearance at Hayward Field and I skipped a day of school to join the protests. Bobby Kennedy came to town. He was campaigning hard in the Oregon primary. His motorcade went down Thirteenth Avenue, in front of El Sombrero and Mama stepped outside to snap off some pictures of the historic event.

A week later Bobby was dead.

My world shattered when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. Mama let me skip school to watch his funeral. I couldn’t think of anything positive to live for.

A massive candle-light parade was planned. Students and protestors from all over the West Coast and the country came to Eugene to participate. Tens of thousands of people filled the streets carrying banners and placards. Young girls wore tie-dyed dresses, and flowers and feathers in their hair. The young men sported beards and long hair.

In the front window of El Sombrero was a large psychedelic poster announcing the upcoming protest. As was his want, Papa was in the thick of the planning. In the afternoons and late at night, the protest planners sat in our restaurant and plotted mischief over cups of coffee and plates of tacos.

The march started at the University and wound down Thirteenth Avenue to downtown Eugene where speakers further incited the crowds. Nervous city fathers decided not to issue a parade permit. The lack of a permit didn’t slow the protest organizers a bit. The march went on.

Mama and Papa closed the restaurant that night to support the protest. They attended the rally on campus, but eschewed the march, they had to get up the next morning to open the restaurant. I walked the route with my candle in hand.

The Eugene police department was woefully understaffed to handle demonstrations on this scale. They made a presence, but were overwhelmed by the sheer size of the crowd. They stood helplessly by while the march began.

Within a few blocks the march turned ugly. Radical leaders incited the crowd. Big business was a target of their anger. First someone wailed about the evils of the military-industrial complex. Then we heard about how The Establishment was destroying our freedoms. There was construction going on down the street and the site had stacks of bricks in front of it. This was unfortunate timing.

Someone picked up a brick and hurled it through the window of the US Bank branch across the street from El Sombrero. The anger of the crowd exploded. Soon bricks were flying through the air. The police moved in, but were overpowered by the crowd. The march moved down the street shattering windows, pulling displays down and generally making mayhem in the streets.

By all standards, the protestors thought that the march was a great success. It ended in front of the Federal Courthouse in downtown Eugene. Speakers with megaphones harangued the crowd late into the night. The sweet smell of pot filled the air. As the wee hours of the morning approached the crowd began to dissipate.

Some of the mob slipped off to grab a few winks at their crash pads or their old lady’s house. Some just found grassy spots along the downtown sidewalks on which to collapse.

The sun rose to reveal the extent of the chaos. Merchants and office workers returned to claim downtown, but there was a trail of damage where the march had passed. Hardly a business was unaffected. Windows had been smashed, storefronts looted, banks and insurance offices fouled.

When Papa arrived at El Sombrero to begin his set up for the day, the street was in ruins. It looked like downtown Berlin in 1945. The pavement was littered with broken glass, articles of clothing dragged from display windows, books from the nearby bookstore, goods from the little drug store down the street. There was no rhyme or reason to the destruction, the protesters were just expressing their helplessness and anger.

El Sombrero survived the night without a scratch. As the march wound past our restaurant, a group Black Panthers formed a human shield in front of our establishment.

“Hey, man, they’re cool,” they told the angry protesters as they approached, bricks and rocks in hand. In spite of the anger and destruction of that night, we remained unscathed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed