Okay, I'm guilty. I admit it. I'm a horrible salesman. I just hate to ask people to close the deal. If I had to make my living selling, I'd starve. Why do I tell you this? Because I've read a couple of books by wildly successful indie authors that say I should ask for the sales twice on each blog post. I haven't done this, so I decided to rectify the situation. Here's the pitch. I'm almost finished with the first draft of the new Ted Higuera thriller, Cyberwarfare. It is a completely stand alone book and you can read it without reading any other of my books, but it takes place directly after The Chinatown Murders. To really get a good understanding of Ted's universe, it would greatly help to read The Chinatown Murders first. Get your copy of The Chinatown Murders today. Well, was that too bad? Driving for LyftBook sales have dropped off significantly in the last couple of months. To make up the shortfall, I took up driving for Lyft. I’ve given over three hundred rides, but a select few stand out. Ducks vs Beavers Everyone knows I’m a Duck. I graduated from the University of Oregon and wear it proudly. All my sweat shirts say Oregon on them and half of my T-shirts are from Oregon. The Ducks big in-state rivalry is with Oregon State University, the Beavers. On Saturday night I picked up four young people in the Gaslamp Quarter of San Diego. They were partying and very (alcohol induced) happy. They got in the car and off we headed to Pacific Beach, about a twenty-minute drive away. It didn’t take long for me to figure them out. They talked about OSU (I thought to myself, Are they talking about the Beavers or Ohio State?). Then they mentioned Beaver Village. I cut in. “Do you mean Corvallis?” They gave a positive response. “If you’re Beavers, I’m afraid you’re going to have to get out of my car,” I said. They were shocked. I turned towards the guy in the passenger seat and held out my green sweat shirt with yellow lettering that said “Oregon” on it. They went mad. We had a great ride, chiding each other’s alma maters until the girl mentioned that she was a Yankee fan. Then the three of us guys turned on her like a school of piranhas. I dropped them off at Pacific Beach and returned to the Gaslamp. My next ride was two young men, one of them deep in his cups. We chatted. They said they were San Diego natives. I mentioned that I came from Seattle. “Oh, I’m familiar with the Northwest,” the man in the passenger seat said. “I went to the University of Oregon.” Once more I showed him my sweatshirt and said, “I’m a Duck.” “I played football for a year,” the drunk in the back seat said, then quickly passed out. We were instantly best friends. We talked football and basketball, discussed living in Eugene, and shared fond memories of our college days. It was a long ride, all the way up to Rancho Bernardo, about a forty-five-minute drive. Passenger #1 decided he was hungry and wanted to stop at McDonald’s. While he was in the restaurant he bought me a Big Mac Jr. – Hey, we were college buddies. It’s funny how much coincidence there is in the world. Who woulda thunk that I’d pick up passengers from both my rival school and my alma mater on back-to-back drives? Sleeping Girl I have two daughters. They are twenty-eight and thirty-three. They’re both strong, capable women and I don’t worry about them too much. Until Friday night. I got a call to pick up a young lady in the Gaslamp. Her destination was the Wyndham Hotel in Del Mar. She was a beautiful young Latina, I’d say in her early twenties. She was slightly inebriated. (Did I say slightly?). She told me that she’d been out partying with one of her girlfriends, but that she’d lost the girlfriend and decided to go home. I think that was probably a good decision. However, as soon as she was settled in the car, the passed out. I drove up to Del Mar in silence. When we arrived, I tried to wake her up. I gently shook her arm. She didn’t stir. I shook harder. Nothing. I shook hard and called her name. She mumbled something. When she finally came to, she screamed and asked what I thought I was doing. I could see the sexual misconduct complaint coming. “Anita (named changed to protect the guilty), we’re here.” “Uhhhh … Okay.” She fumbled with the door and finally managed to get it open. She staggered into the hotel lobby. I watched to make sure she was going to be all right. Fortunately, a uniformed woman saw her staggering around the lobby and managed to catch her before she fell. I’m sure the hotel employee got her to her room safely. The moral of the story: that girl got lucky. She was totally defenseless in my car. Her short skirt was hiked up around her panties and her low-cut top wasn’t hiding much of anything. When she got in the car, my paternal instincts kicked in. What would have happened if she was picked up by someone less scrupulous? My writer’s imagination ran away with me. She could have been driven to some remote location and taken advantage of, maybe even killed. She was in no condition to defend herself. As a matter of fact, Dawn and I have been talking about writing a book called the Uber Murders about just this subject. How many young girls like Anita are out there every night? They’re dressed to kill and head out to drink. Once intoxicated, they are at the mercy of every predator in the neighborhood. I’m just glad that this story ended happily. Day Off I started driving early on Sunday because I wanted to be home in time for the 60 Minutes interview with Stormy Daniels. (I love a good sex scandal) I was planning on taking the day off, but needed six more rides to reach Lyft’s bonus level. It was worth one hundred and five dollars to get those six rides. My first ride was in Little Italy. A nice couple wanted me to take them home to Ocean Beach, about a mile from where I live. After dropping them off, I got an immediate call for a ride only a few blocks away. Unfortunately, I was on a busy arterial street when I got the call and I’d already passed the turn. I circled around the block to come back and pick up my ride. Circling the block in Ocean Beech is no mean task. I had to go up into the hills where the streets are not in a grid pattern. After several right turns, I was back on West Point Loma Boulevard and on my way to the pick-up. When I arrived there, a young lady, dressed in a tank top and very short cutoffs, awaited me. She was angry. Why had it taken me so long? Why was I driving around in the hills instead of coming to pick her up? She was very worried about getting to work on time. She just started a job in the Gaslamp as a server and her boss does not take kindly to people being late. I assured her that we would make it on time and she rode the rest of the way without saying a word. When we arrived at her destination, there was a closed sign in the window. “Can you just wait here for a minute?” she asked. “You can keep the meter running.” No problem. I’m there to serve. “Oh my God,” she said. “Today’s my day off.” She held her head in her hands. “I got so hammered last night, that I didn’t know what day it was.” She pulled out her cell phone and called her husband who was out playing golf. He agreed to come down and pick her up, so I let her out and drove on. Another day messed up by the Demon Rum. Sex Talk

I’ve noticed that there are three types of passengers on Lyft. There are the ones who engage you in conversation. My sharp mind, rapier like wit and gregarious humor allows me to interface with these people and keep them laughing all the way to their destination. Then there are those who talk among themselves and ignore you. They must think that I’m in the cone of silence because they talk about the most intimate things and even fight while I’m sitting right there with them. They would never have these conversations in a restaurant booth, for instance, with strangers near them. The final kind are the ones who sit in silence the whole way. I try to engage them, and they answer in mono syllables, so I give up and let them ride in peace. If you’re under eighteen or are prudish, you can stop reading here. I picked up two good looking women and a movie-star gorgeous man in Little Italy. After the requisite pleasantries, they drifted off into their own conversation. They didn’t smell like alcohol, but they were obviously high on something. Their voices were loud and inhibitions non-existent. They stared out by sharing how drunk they were last night. Then the conversation got sexual. It was obviously that all three had been sleeping together. No problem, I thought. To each his own. Girl #1 mentioned their bet and the conversation got good. The bet was who could have sex with the most men in twenty-four hours. The man acted as the moderator in this bet. Girl #1 said, “I want to sleep with three guys at the same time. I haven’t done that before.” “Oh,” says girl #2, “You’ve gotta. It’s so much fun. The most I’ve ever fucked at the same time is four.” “Then I’m going to sleep with five tonight.” (I don't think there was much sleeping going on.) The conversation went on. My ears strained to pick up every word. This was better than a porn movie. “You’ve got to promise me to tell me all the details in the morning,” the man said. “If you sleep with three guys, I’m going to call you triple crown. If you sleep with four, I’ll call you grand slam.” He went on. When he got to eight he said, “If you sleep with eight guys, I’ll call you octopussy.” They all broke up. Girl #1 kept the ball rolling. “I’ve already got a head start on you.” “What do you mean?” “Last night I went home with that guy at the bar, I don’t remember his name. I woke up early, around seven am, and he gave me a ride home. On the way, Chris called me. He wanted to come over and cuddle. “I had the guy drop me off at a coffee shop. I got coffee and pasties and called an Uber to take me home. I’ve already done two guys today.” And so it went. I couldn’t believe these girls. I’ve read books and seen movies with people like this, but I didn’t know they existed in real-life. Where were they when I was young? The last time I wrote to you, I introduced myself. My name is Lilly and I’m a Harlequin Great Dane. That’s the best kind of Great Dane. About five months ago, I got a new Mom and Dad and a new home. On a boat, of all places. Now, that’s not the kind of lifestyle I envisioned for a trophy dog like me. I kinda got used to the boat. Sure, getting up and down was a hassle and it was a long walk to the park where I could go potty, but it had its perks. I made lots of dog friends on the other docks and Mom took me for long walks in the park and at the dog beach. I love playing in the ocean and run around and around until I can’t run anymore. There were some weird things about living on the boat. We had a long dock we had to walk up to get to the parking lot. There were these shiny T-shaped things all along the dock with leashes tied to the boats. They kept getting in my way. Another funny thing was Frazier Crane. He’s a big bird that lives on our dock. He’s kinda like a giant chicken with long legs and a long neck. He’s really friendly and isn’t afraid of me. I can walk right up to him. He has these giant wings and with one or two flaps he can be airborne. When he comes in to land, he practically hangs still in mid-air. The boat was a nice, snug den. No one could sneak up on me, it was safe and secure. I was getting kinda used to it when my world was shattered again. One day Mom brought home a lot of boxes and they started packing everything on the boat. Then they took the boxes and disappeared for hours. For the next two days I had lots of time by myself, but the good news was that there was no one around to tell me to get off of the big bed in the aft cabin. The next day, Mom loaded me into her SUV, we call it the Queen Mary because it’s so big. I like the QM because it has a big flat area in the back and a long seat in front. Sometimes Mom lets me ride up front with her. This day I got to ride up front because the back was packed to the ceiling with boxes. We drove to a park with lots and lots of huge houses. I was afraid she was taking me to new parents. I have had so many, that I don’t want to change again. She took me out of the car and to a flight of stairs. These stairs were different than the companionway ladder on the boat. I could get up and down that by myself, but these stairs were scary. The were slanted and went way up to the second floor of the big house. Mom made me go up. It was difficult at first as I tried to figure out how these things worked. We got to the landing on the top and Mom said, “This is your new home.” She opened the door and went in. I stayed outside, not sure what would happen in there. Everything was a mess. The apartment was filled with boxes. I couldn’t find a place to lay down. The apartment on land seemed smaller than the boat, but as stuff got put away, we had more room. Mom was totally stressed out, it made me want to take a nap. But my big concern was where was my food bowl? My water bowl? After a couple of days of unpacking, Mom took Dad away. I don’t know what he did that was so bad, but I decided to be careful myself, so she didn’t take me away. I got left alone for a long time, then Mom came home without him. The next day, she went back and picked him up. Now he spends all his time in bed. He’s always limping around with a walker and can’t carry anything. I don’t know if I’ll ever get any fun out of the old guy. Mom spent the next few days putting the stuff in the boxes away and little by little, there was room to move around.

People are funny. I watched Mom unpack. She took armfuls of towels out of the boxes. What did she need with so many towels? You can only dry yourself with one at a time. She unpacked a funny looking wooden box and put it on top of the china cabinet. The strange box had a glass door and under the door was a metal circle with little arms on it. Every so often it made strange ringing sounds. What in the world did she need that for? Eventually, we got moved in and it began to feel like home. I found my food bowl and best yet, I discovered that my food bag is in the closet. Every now and then, Mom doesn’t lock the closet door. When I notice this, I pretend not to know it and go lay down on the couch. When no one is around, I push the door open and have a party in my food bag. We live five minutes from the dog beach at Ocean Beach. There are lots of other dogs and some of them are nice, but I haven’t made any real good friends. We chase each other, and they like to play with this round thing. Their people throw it and they chase after it, then bring it back to their people. Mom wants me to play this game, but she hasn’t explained the rules yet. I run after the round thing and pick it up, but it’s round and slips out of my mouth. I throw it up in the air and try to catch it like the other dogs, but it always falls too far away for me to catch. Eventually, I give up and bring the thing back to Mom and she throws it again. Doesn’t she understand that I don’t like this game? She keeps embarrassing me in front of the other dogs. I’m getting along better with Dad. He gets out of bed now, walks faster and always has food for me. He eats a lot and takes more than he can eat, so I always get something from his plate. Lately, Mom’s always at work, so I have to settle for Dad. He takes me out for short walks, but no fun stuff like Mom does. I have less play time and have to hang out with a boring old man. That’s about it for today. I’ll write again as soon as I can. I want to have something interesting to say when I do. Thanks for listening to me and be sure to buy one of Dad’s books. We need the kibbles. My name is Lilly, I think. I got really confused about my name for a while, but my new Mom and Dad are calling me Lilly all the time now, so I think that’s my new name. I had a previous home and they called me Riley. I got used to it, but when I moved in with my new Mom and Dad, Dad kept calling me Lilly walking around singing a song called “Darling Lilly.” I’m a Harlequin Great Dane. That’s the best kind. I’m a beautiful young girl (I don’t want you to think I’m stuck up, but I’m just being honest here.), white with black markings. Mom says that my markings are perfect for a show dog. As a matter of fact, I was being groomed to be a show dog. I guess that’s kinda like a little girl being groomed for the beauty contest circuit. I had another life, but it wasn’t much fun. I lived in a kennel most of the time. There were three other male dogs in the house and they were always aggressive. One day, when no one was at home, one of them broke into my kennel and did unimaginable things to me. #MeToo. I ended up pregnant, but it didn’t go well. I got really sick and my parents took me to the hospital. The doctor put me to sleep and when I woke up, I had bandages all over my belly. I lost the puppies and had my female parts removed. It took me a while to recover, then my parents couldn’t keep me anymore. I was moved around to a couple of foster homes and ended up in a Great Dane Rescue place. One day, a pretty blonde lady came to see me. It didn’t take long for me to win her over. I went home with her, but when we got there, it wasn’t what I expected at all. My fairy tale dream was to live in a big house with a loving family, a Mom a Dan and 2.3 kids. The house would be three bedrooms with 2.5 baths and have lots and lots of yard with green lawn and trees and squirrels to chase. That wasn’t what I got. As we pulled into the parking lot Mom said, “Lilly, this is your new home, Chula Vista Marina.” This wasn't a big house with 2.3 kids. My new mom put me on a leash and let me through the paved parking lot. We walked a long way and came to a gate the led to a long bridge. We went through the gate and walked all the way to the end of the bridge. Mom stopped in front of this big white thing with two trees growing out of it floating in the water. She wanted me to jump up on it. No way. It didn’t look safe. It just sat in the water. What if it sank and I was on it? Then I’d be in the water. She took me to an opening in the fence around the edges of the white thing and wanted me to climb a little ladder to get up. Not me, baby. She put my front paws on the white thing, but I turned away. After several tries, she was fast enough to get my paws up, then lifted my bottom. I had no choice but to go ahead. I was on the white thing. It was weird. There were obstacles all over the ground. The ground felt hard, like the pavement in the parking lot. There was a kind of little house on the ground. I’d never seen anything like it before. It had a real roof and windows, but it wasn’t as tall as I was. I could look right over it. Mom climbed up with me and opened a little door in the house. There was a long ladder leading down into a dark hole. Mom called Dad and they tried to get me to go down in the hole. Uh-uh. If I was worried about being on top of this thing, no way I was going down into it. What if it sank and I was stuck inside. I couldn’t get out. I’d drown.  In the pilot house of my new home In the pilot house of my new home Dad put a long step about halfway down the ladder. Mom tried to get me to go down. Not in this lifetime. Dad came up the ladder. Mom went down and held my leash. I couldn’t turn away. Dad, the evil bastard, lifted my hind end and forced me into the hole. There was nothing I could do. I had to go forward and land on the little platform. My momentum carried me forward and I had to jump down onto the wooden floor. I was entombed in the death trap. That was my new home. If I went forward, I found a cabin with a couple of beds, but they were so high up, I couldn’t jump up into them. Mom lifted me up a couple of times, and they were plenty comfortable, but then Mom went to another room and left me alone. I wasn’t buying. She was leaving me there to die when the thing sank. I jumped right down. In the middle of this floating house, there was a kitchen and table. Dad spent a lot of time sitting at the table doing something with his lap top. I never understood what was so fascinating. If I went further back, there was another room. It was big and comfortable. There were seats all around it and above and behind the seats there were beds. I loved the big bed in the middle, but the old ogre wouldn’t let me lay there. Whenever they left me alone though, I jumped up in the big bed and took a nice snooze. I learned that this floating house was called a boat. I got familiar with it and found out that the front part was called forward and the back part, aft. The kitchen was called a galley and the bathrooms were called heads. (I never figured that one out.) There was something wrong with Dad’s leg. He hobbled around on the boat and whenever we left the boat, he had a metal stick that he leaned on to walk. It wasn’t much fun. I couldn’t run with him the way I did with Mom. One day, when Mom was at work, Dad was going to take me outside. He had a plywood platform that he attached to the ladder with clamps. We could both stand on this platform and he helped me climb up to the deck. It wasn’t long before I learned to climb up and down the steps by myself, but this was early on. I jumped up onto the platform and the old man climbed up too. Then something happened. There was a loud crack and the platform fell free. Dad landed on the deck and smashed his head into the cabinet under the chart table. I fell on top of him. I thought it was very nice of him to fall first so that I had something soft to land on. It scared me out of my mind. I ran into the aft cabin, jumped up onto the big bed and curled up. Dad lay on the floor with his head stuck inside the cabinet. I thought I should check on him, so I climbed down and walked to the pilot house. He just lay there. I poked at him with my nose and he groaned, laughed and rubbed my ears. Eventually, he got up and fixed the platform, so we could go out. He climbed up on it and it didn’t fall, so I decided to give it a try. I gingerly jumped up on the settee next to the ladder and tested my weight on the platform. It held. We climbed out of the boat and went to the park, so I could run and do my business. We lived on the boat for about three months. I had dog friends on each dock and Mom made play dates for us. I found my favorite places to poop and pee, then my world was turned upside down again. Dad had to have an operation to fix his knee and we needed to move off the boat. What a nightmare. In keeping with my restaurant stories and family adventures, I'm going to introduce you to my brother Jon. Jon is the middle of three brothers and always the wiseacre. He made my life miserable as a teen, but turned out OK as an adult. My older sister Quita died in a boating accident when I was eleven years old. My brothers, Jon and Jim, were six and five years old. That left me the oldest child. As the oldest child, I always had to blaze the trail. When I wanted to do something I usually had to battle stiff resistance from my parents, by the time Jon and Jim were old enough to do what I had wanted, the precedent had been set and my parents’ resistance worn down. Jon and Jim didn’t even have to put up a fight. I wanted a motorcycle the year I graduated from high school. (Spiderman's alter ego, Peter Parker, had just bought a motorcycle, so I had to have one.) Mama thought it was a terrible idea and we fought a long hard battle before I finally was allowed to buy a bike. The following summer I wanted to take my bike on a road trip. It was (and still is) my dream to visit each city with a major league baseball team and see a game in each ballpark. Mama was adamant. I would not go. I was too young and the trip was too dangerous. In the summer between his junior and senior years in high school, Jon got to take my trip. Well, it wasn’t exactly my trip, but he did take a road trip with his friends without parental supervision. At dinner one Sunday evening he announced “I'm taking a trip to Mexico this summer with two of my friends.” Neither Mama nor Papa put up a struggle. I guess where I went wrong was that I asked if I could. Jon just told my parents that he was going. He and his friends took Mama’s Chevy II Nova station wagon and drove down the coast. They crossed the border at San Diego and went down Baja until they ran out of money and returned home on fumes. The following summer, we opened the La Posada Mexican Restaurant. Papa and I took on the job of remodeling a free-standing restaurant building to make it look like a Mexican inn. To complete the job, we needed to make a trip to Southern California and Tijuana to buy decorations and equipment that wasn’t available in Eugene. While Jim and Papa remained in Eugene, working on the restaurant, Jon went on the trip with Mama and me to California. My uncle Juan had lived in Tijuana for two years when he was waiting to cross the border into the U.S. He knew his way around town. He was excited about our visit and anxious to show us his Tijuana. He knew how to bargain with merchants and what was a good deal. With his help, we loaded down the Nova wagon with all sorts of lamps, decorations and equipment. It was a long, hard day of shopping. As the afternoon wore on, Juan wanted to take us to his favorite restaurant. We wound through narrow, twisting streets to an unassuming white building along a high sidewalked street. It was typical Mexican architecture with whitewashed stucco outer walls, tile roof and lots of wrought iron. The restaurant was build around a central open-air courtyard. In the center of the courtyard was a fountain, bougainvilleas and other tropical plants helped to lend an air of cool ease. Wrought iron chandeliers hung from the ceilings and murals were painted on walls depicting Aztec legends. In the courtyard wooden tables and chairs with white table cloths awaited us. The staff was very gracious. They knew Juan and treated him like a king. During his years waiting to get a visa to enter America, he had washed dishes in this restaurant. Now, twenty years later, he was a well to do American contractor. He had made it out. The menus were all in Spanish; this was a Mexican restaurant for Mexicans. That presented no problem for us, because we all spoke Spanish to some degree or other. This restaurant specialized in meat dishes, not the traditional enchiladas and tamales that you see along the border in most restaurants. I ordered chile verde, Mama ordered carne asada, Juan and my aunt Mellie ordered bistec ranchero, Jon ordered chiles relleno. After the orders were taken and the waiters left us alone, Jon began to tell us the story of his trip to Mexico the previous summer. “We’d been driving for hours,” he began. “There were no signs on the road and it just kept going on forever. We were lost and needed directions so we stopped at a little roadside restaurant for help. “When we went into the restaurant, it was deserted. There were a few miserable miss-matched tables and chairs under a palapa roof over a dirt floor in front. In the run-down little building was the kitchen.” Jon was the only one in his group that spoke Spanish so it was up to him to ask for directions. “We heard voices out back so I went through the kitchen to find someone. As I walked though the kitchen, there were some open garbage cans with flies buzzing around them. I don’t know why, but I looked in the garbage cans and there were dog’s heads in them.”

Everyone lost their appetite. Mama and Mellie made choking sounds and reached for their bottles of pop. Then the waiters brought the food to the table. The meal lived up to Juan’s promise. The plates were artfully prepared and a feast for the eyes. Jon enjoyed every bite of his chiles relleno, which did not have any meat. No one else, except me, could eat their lunches. I didn’t care if the chile verde was made with dog or monkey, it looked good and smelled wonderful, so I dug in. The pages on the calendar turn and we head into the cold winter months. The year comes to an end and we begin the holiday season. This year, I thought I'd share one of my favorite Mama stories. She wrote this decades ago  A traditional Mexican Thanksgiving. A traditional Mexican Thanksgiving. My first attempt at a traditional Thanksgiving dinner was during World War II. This was a time when my Mexican-American brothers and sisters and other male relatives, and friends, were slowly awakening to the realization that enjoying the privileges of a bountiful American brought with it responsibilities, as well a s certain changes in attitude. Several Mexican-American families, who had received “Greetings from the President of the United States,” had already sent their sons off to war. As for myself, having been raised in a strict Mexican tradition, I felt it was also time to experience something of the American tradition. And what better time to start than on Thanksgiving Day? Or so I thought. Not many of the Mexican families that I knew celebrated Thanksgiving. I had learned about roast turkey and dressing, mashed potatoes and gravy – and the Pilgrim Fathers – in the history books at my school in Costa Mesa, California. I told my parents about Thanksgiving Day (my parents knew nothing of U. S. history, expect that California was once Mexico). I told them about the Pilgrims, and about the Indians, and how they had all sat down at the same table to eat roast turkey, in 1621, at a place called Plymouth Rock. With the all-knowing wisdom of the typical Mexican head-of-the-family, my father replied, “Our family had nothing to do with this Plymouth Rock, or Thanksgiving, or Pilgrims. Our heritage is Cinco do Mayo and the 16th of September.” That’s how it was that all through my childhood. I listened to the American kids talk about their turkey dinner on Thanksgiving, and I had vowed that when I grew up, I would have a turkey feast on Thanksgiving Day. Finally, the day arrived. I was a young lady now, married and on my own; it was time, I thought, to begin the American tradition. By this time, all of my brothers and sisters had large families. I made arrangements with our mama to invite all the family. I would bring the dinner – our first Thanksgiving family dinner. How excited I was in those last few days before Thanksgiving! I bought the biggest turkey in the store, along with all the ingredients to make the traditional American dinner. I read American recipes until I was tired of reading. This feast was to be just as it had been for the Pilgrims and Indians. At last, Thanksgiving Day arrived. After much planning and labor, the dinner was prepared. My husband and I transported the huge dinner to the home of my parents, where all my sisters and brothers and their families had already gathered. Since I told them that it would be a traditional American dinner, excitement and anticipation ran high. When Mama and I sat the beautifully browned turkey on the table, I’m sure the “ahs’ and “ohs” must have been heard all over Costa Mesa. There was sage dressing, mashed potatoes and giblet gravy, cranberry sauce, green peas and fruit salad. On Mama’s cabinet, sitting in a row, were five golden brown, tantalizingly plump pumpkin pies. The children were beyond themselves with excitement. They had never seen, much less tasted, such attractive food. Oh yes, they had eaten turkey before, but it had been just small pieces, smothered in mole sauce. But here, in the center of their grandparents’ table, was the festive bird in its entirety – just waiting for a drumstick to be carved. The children devoured the food with their large dark eyes. My husband undertook the job of carving and serving the turkey – no small job, considering the number of hungry children, and their impatience to be served. At last, everyone was served, But, something wasn’t quite right. Looking around, I saw a disappointed look on everyone’s face. It was such delicious food – what had gone wrong? But no one spoke. Was all the planning and all the work – to say nothing of my dreams of a traditional dinner – to end in disappointment? It appeared so, because it was obvious that no one like it. We nibbled at the food for a few minutes. From the corner of my eye, I could see the children looking to their mothers for help, and the mothers threatening the children with stern looks. It was a tense time and it seemed that an explosion would burst at any moment. Finally, it happened. Little Angelina couldn’t stand it any longer. Looking pathetically up to Grandma, she said in her most pleading voice, “Aubelita! No tortillas? No frijoles?”

Then Juanita, to her mother, “Mama! No tortillas? No Frijoles?” Now it was Virginia’s turn, “Mama! No tortillas” No frijoles?” Then baby Margarita, whose vocabulary was limited to three words, “Mama, tillas? . . . joles?” I looked around the table. Everyone’s eyes were on Mama. She looked at me, and our eyes met, and we both knew and understood. As always, Mama was the salvation. Rising from her chair, she went to the cupboard, where, miraculously, there was a pot of warm beans and a large basket of fresh tortillas. She set them on the table next to the turkey, along with a molcajete of chile verde. One by one, smiles lighted the troubled faces of the children, as the frijoles and tortillas were passed around to take their places beside the American Thanksgiving food on their plates. That long-ago Thanksgiving, during World War II, was the first time I ever saw a roast turkey smothered with chile verde. Mama praised it, and Papa grudgingly admitted that “mole Americano” (American gravy) was pretty good. The children, who liked Grandma’s tortillas and frijoles the best of all, wrapped their turkey and frijoles inside the tortillas. After dinner we talked abut the first Thanksgiving dinner in Plymouth in 1621. We all agreed it was an interesting story, but not nearly so exciting as the stories told by my father about the Aztecs and the Spaniards – of whom he was a descendant – and about his childhood in Mexico. That Thanksgiving dinner, with turkey smothered in chile verde and wrapped in tortillas, was the very first that my entire family enjoyed together. Since then there have been many more traditional Thanksgiving dinners for my brothers and sister and their children and grandchildren – but, for me, none so memorable as the one when I first realized that my family was a people in transition between two heritages. I've been telling you stories about my growing up in the back end of a Mexican restaurant. This week I'm diverting slightly from my theme. I'm still talking about Mexican food, but this time, I give you my personal history with tacos. My first memories of tacos were of street vendors in Tijuana. We rarely ate out and there were few Mexican restaurants in Southern California in the early Fifties. There certainly weren’t any Taco Times or Taco Bells with their American tacos. When we visited Mexico, I was fascinated by the street vendors. They were usually older women, dressed in peasant-style blouses with red and green threads in the collar and sleeves, bright skirts and rebozos (shawls). Their stands consisted of a table with a propane burner on it, a frying pan full of dirty looking oil, crockery bowls full of toppings, a big bowl with taco meat and a stack of handmade tortillas. The taco meat was ground beef with chilies, onions, potato and spices in it; it smelled wonderful. To make the tacos the vendor folded the tortillas around some taco meat then sealed them shut with tooth picks. She fried the tortillas with meat in the dirty oil. When it was good and crisp, she removed the taco and patted it down with a dirty-looking cloth dish towel to remove the excess grease. The toothpicks were removed and shredded lettuce, fresh farmer cheese, salsa and tomatoes were added. We never ate from one of the taco stands, but they looked and smelled wonderful. In the restaurants in Tijuana, when we ordered tacos, we got a similar dish. I had no doubt that it was made is the same fashion. The few times we did eat in a Mexican restaurant in Costa Mesa or Santa Ana, the tacos were similar to what we saw in Tijuana. In most of these restaurants, there were women making tortillas by hand and cooking them on a hot grill where the customers could see them. The one difference between the tacos that we saw in Southern California and what we saw in Mexico was that in the US we could get tacos with picadillo, shredded beef, rather than the ground beef we saw in Mexico. Then modernization hit. As Papa would say, some smart Yankee figured out how to automate the process. Tortilla machines were developed that produced hundreds or thousands of tortillas per hour. The tortillas were all uniform in size, shape and taste. Shortly after the introduction of the tortilla machine, we started seeing hard-shelled tacos in restaurants. An industrious restaurateur discovered that he could save labor dollars by inventing a mold that would hold six or eight tortillas at a time, and fry them into identical, crisp taco shells. The industry got a hold of his mold and all the restaurants began offering hard shell tacos like we know today. Then Taco Time and Taco Bell entered the market, offering Mexican fast food. They swept over the nation, introducing America to the American version of tacos. Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing against American tacos. I have eaten, served and enjoyed my share in my lifetime, but what we see in most restaurants here is not what is called a taco in Mexico. My introduction to real Mexican tacos came in Guanajuato, Mexico. The city of Guanajuato is the capital of the state of Guanajuato. My grandfather grew up there before he came to the United States and my mother wanted to visit her father’s home town. In 1981 Connie and I took Mama to Guanajuato, Guadalajara and Puerto Vallarta on the trip of a lifetime. Guanajuato is built in a canyon, high in the Sierra Madre Mountains of central Mexico. It is a long day’s drive south of Guadalajara. I had seen taco stands in Guadalajara, but did not have the nerve to order from street vendors. By the time we got to Guanajuato, my resolve broke down. We got in after the restaurants closed for lunch and before they opened for dinner. We were starving. The bus that we rode to Guanajuato made a lunch stop in San Juan de los Lagos, but the bus terminal was so disgustingly dirty that we couldn’t bring ourselves to eat there. By the time we arrived in Guanajuato, we were starved. After checking into our Sixteenth Century hotel we decided to walk about the town. As we passed the taco stands, with their smells of roasting meat, onions, garlic and chilies, I broke down. I couldn’t resist any longer. The taco stands of Guanajuato sold tacos al pastor, camp-style tacos. They used a vertical-spit barbeque to cook the meat; much like is used to cook the meat for gyros in Greek cuisine. Onto the vertical spit, a layer of pork was added, then a layer of onions, then a layer of pork, etc. The spit was about two feet tall and the meat was about a foot and a half in diameter. A fire burned behind the meat and the heat spread by bricks stacked in front of the burners, much like we use lava rocks in the bottom of our gas grills in this country, cooked the meat. The meat/onion rotated on the spit in front of the hot bricks and gave off an enticing aroma. As the outside layer of the meat cooked, the vendor took a long, sharp knife and sliced it off in thin sections, exposing the un-cooked meat underneath to the heat. As the day wore on, the stack of meat got thinner and thinner. At the bottom of the spit, the meat and onions lay in their own juices and absorbed even more flavor. When a customer ordered tacos, the vendor scooped up the meat and onions into four-inch diameter corn tortillas, topped them with cilantro, salsa and fresh chopped onion, then wrapped six tacos together in brown butcher paper packets. “Let’s order a package of tacos to hold us until dinner.” I suggested. Mama and Connie were starving too and had no objection. We took our packet of tacos and sat down on a park bench. I had never tasted anything so wonderful in my life. The savory flavor of the meat, along with the freshness of the cilantro and the sweetness of the onions exploded in my mouth. We quickly polished off the package of six tacos. “These are wonderful, let’s order six more.” We never made it to a restaurant for dinner. I ate a dozen of the little tacos on the park bench beneath the setting December sun. From then on, where ever we traveled in Mexico, I sought out taco vendors to sample their wares. My favorite tacos are tacos al pastor, Connie’s favorite were tacos carbon, made with carne asada. Our local taqueria in Lynnwood sells wonderful tacos de carnitas. They also have tacos de lingua (beef tongue) and tacos de cabeza de cerdo (meat from the pig’s head), I haven’t tried these. These tacos are all made with the desired meat, then filled with chopped onion, cilantro and salsa. A far cry from American hard-shelled tacos. In my humble opinion, the best tacos that I ever ate are at the Grand Central Market in downtown Los Angeles. The taqueria in the Grand Central Market is located right next to the stand where a giant tortilla machine produces thousands of hot, fresh tortillas per hour. When I was growing up at El Sombrero, the best thing in the world was tortilla day. Usually once a week or so, Mama fired up our tortilla machine to make tortillas. We kept a bowl with melted butter and a brush sitting on top of the machine. As tortillas came off, we brushed butter on one, rolled it up and munched it down. It was the best snack imaginable.

Seeing and smelling the tortilla machine in the Grand Central Market brought back all my childhood memories. As the tortillas rolled off the machine, stacks of them were passed, hot and fresh, to the taqueria next door. The staff in the taqueria made tacos from the still warm tortillas. The taqueria keeps the meat for their tacos on a steam line. They have carne asada, carnitas, pork for tacos al pastor, fish for fish tacos (I could never get used to that one) etc. As you order, they take two fresh tortillas, slap on the meat, add cilantro, onion and salsa and hand it over the counter for a very reasonable price. No normal person can eat more that two tacos. We usually order one, take the outside tortilla off and make a second taco out of it so that we can handle all the fillings without spilling all over our clothes. On the way out of the Market there is a fruit smoothie stand run by an older Mexican woman. We always buy two tacos, fruit smoothies and sit at the tables just outside the entrance in the sun shine. We are just across from the Angel Flight Trolley that runs up Beacon Hill and get to do some serious people watching while we eat. After all, this is LA. I'm continuing on with the theme of growing up in the back end of a Mexican Restaurant. This week I take you to my high school years. If you're enjoying these stories, don't forget to drop me a line. Hearing from you always encourages me to do more Click here to send me a note.  Prepping for a friend's party Prepping for a friend's party The El Sombrero Restaurant had been open for a couple of years. I was in high school by this time. Every day after school, I rushed to the restaurant, did my homework in a booth in the back, ate a quick dinner and was ready to cook dinner shift. My shift began at five pm and ended when we closed at nine pm. Closing was not just locking the doors. At the end of each night, all the food had to be stored in the refrigerator, the steam and cold tables broken down and cleaned, the grill cleaned, the dishes, pots and pans all washed and put away and the floors swept and mopped. I got pretty good at cleaning up at the end of the shift. At eight thirty, if we weren’t busy, I started pulling the food from the steam table and storing it in plastic containers. If an order drifted in, I could prepare it from the containers. By nine o’clock I had the steam and cold tables put away and clean and the dishes all washed up. That left the floors. I could sweep and mop the kitchen floor, but if there were customers in the dining room, I had to wait until they left to clean the dining room. The waitresses were responsible for tearing down and cleaning the dining room and service areas. When the last customer left, I broke down the til, then rushed to clean the floors. My goal was always to get out as quickly as possible so that I could get home and get some sleep before I had to get up for school in the morning. Breaking down the til was an easy task. First I would have the cash register total the sales for the day, then remove the cash register tape and replace it with a fresh tape if needed. Then I took out all the bills and checks and put them in a bank bag. Finally, the coins went into separate envelopes so that they were easy to count in the morning. Papa’s favorite job was to count the money and make out the bank deposit. He could feel the progress we made each day by counting out the nickels and quarters. We were a real seat-of-the-pants, mom and pop operation. We didn’t have a safe in which to store the money each night. When we first opened the restaurant, Mama closed every night and brought home the receipts with her, then Papa took the money back to the restaurant in the morning when he went in to open. Somewhere along the line we decided that it wasn’t a good idea to be walking around late at night with all that cash on us. By all that cash I mean a hundred dollars or so. We put about twenty-five dollars in the til every morning to start the day and our goal for the day was to take in more than one hundred dollars. On a really good day, we might do one hundred fifty or more dollars. When we realized the jeopardy that we were in, carrying all the cash around, Papa came up with a solution to the problem. We had two plastic thirty gallon trash cans that we used to store beans and rice. Each can would just hold a one-hundred-pound sack of beans or rice. Every night when I closed, I buried the bank bag with the money in the bean can. Our reasoning was that no self-respecting thief would ever think to look in the bean can for money. It worked, well we were never robbed so we don’t know if it worked or not, but we never lost any money. After the til was broken down and put away, I swept and mopped the dining room floor while the waitress washed up the last customers’ dishes. By closing time, we were always anxious to go home. The waitress knew that she would be taking no more tables and there would be no more tips for the night. I couldn’t wait to get out of there. On some nights, when the last customers of the day lingered over their meal, I swept the floor in the other side of the dining room and sing “Perfidia.” I have possibly the worst voice in human history. My singing always cleared the dining room so that we could go home. We gave each combination plate dinner on the menu a name. The El Sombrero had an enchilada, a tamal and a taco. The El Estudiante (the student) had an enchilada and a taco. The El Gordo (the fatso) had an enchilada, a tamal, a taco and a chile relleno. That was too much food to fit on one plate, even with the big platters that we used, so we put the chile relleno on a six-inch side plate. The El Gordo was our top of the line meal, costing two dollars and ninety-five cents.

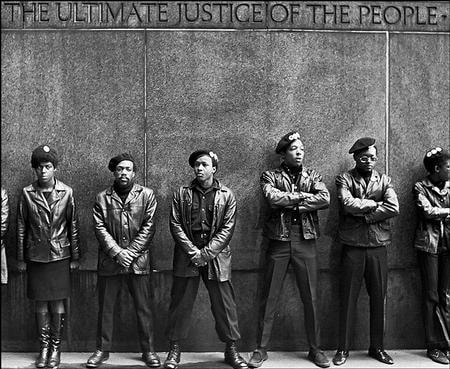

At El Sombrero we made chile rellenos to order. When a waitress brought in an order with a chile relleno, she called it out so that the cooks would know to get it started ahead of the rest of the meal, so that all the food would be hot and ready at the same time. In the back of the kitchen, we had a food prep area that Papa dubbed “the glory hole.” In the glory hole, we separated the egg white from the yolk for the chile relleno and beat it with an electric mixer until it was stiff. Then we gently folded in the egg yolk back in. When this was done, we added a green chile, stuffed with cheddar cheese. In the mean time, we had lit a fire under a cast iron egg pan to heat the pan. When we had the chile and egg ready, we poured them into the egg pan to fry. A few minutes on each side turned them a golden brown. After the egg was cooked, we scooped the chile relleno out of the pan with a spatula and put it on the side dish. Then we smothered it with ranchera sauce, topped it with cheddar cheese and put it in the broiler to melt the cheese. While the relleno was cooking, it puffed up like a soufflé. When it was ready, the waitress had to serve it immediately so that it would not cool down and loose the air. Mama always pounded into us that “you eat with your eyes.” The presentation of the food was as important as the taste. On this particular night Red Mary was closing with me. We had four Marys working for us. There was Big Mary, Little Mary, Red Mary (because she had red hair) and Maria Canadiana (Canadian Mary). When my mother posted the schedule each week, she used these names to identify them. “El Gordos a pair,” Mary called as she hung up a ticket for me. The last party of the night slipped in at ten minutes ‘til nine. They were a young attractive couple, he was wearing a suit and tie, she was in a nice dress, unusual attire for our regular customer base. They ordered the most complicated dinners on the menu and I was going to have to make chile rellenos for them. “Ay como friegas,” I swore under my breath. Not only did this couple have the audacity to come in at closing time, they ordered the biggest meal on the menu. I dropped back to the glory hole and started separating the eggs for their chile rellenos. As the chiles cooked in their little cast-iron skillets, I made the enchiladas and popped them under the broiler. When the enchiladas were cooked, I unwrapped two tamales from their hojas (corn husks) and placed them on the plate, covering them in a rich red chile sauce, then quickly made two tacos. By this time, the chile rellenos were through cooking in the broiler and four plates were steaming under the heat lamps, waiting for Mary to pick them up. I pulled the ticket from the clip, rang the bell on the counter and shouted “Mary, order up,” in best diner fashion. All the plates we served were hot from the oven. Our waitresses, using pot holders, could only carry two plates at a time. Since the El Gordo took two plates to serve, that meant that Mary made two trips to the table. Red Mary grabbed the large platters and ran towards the dining room. Our goal was always to serve the plates while they were still sizzling. Since it was now after closing time and we were anxious to clean up and go home, I mopped the kitchen and half the dining room already. While Mary was serving the first two plates to our late customers, I grabbed the mop and quickly mopped the service area. Just as I returned the mop to the bucket, Mary came back to pick up the side plates with the steaming chiles rellenos. She grabbed the plates and turned to rush them to the table while they were still puffy from the hot air. As she took her first step towards the dining room, she slipped on the wet floor and went skidding. Both plates flew from her hands as she landed on her back side. The first plate went high into the air, turning over and over like a punted football. It made a perfect circle as it went straight up, then dropped back down into her lap. Mary didn’t have time to think, just react. Somehow, she had managed to hang onto the two potholders that she was using to serve the hot plates. As the hot plate with the chile relleno dropped into her lap, she grabbed at it and plucked it out of the air. The second chile relleno plate took a different course. It flew out of the service area and across the dining room. It arched through the air, flew over the lady’s head and skidded to a halt on the table, in front of the gentleman. Mary could not have tossed the plate to such a perfect position if she had tried. “Now that’s fast service,” the man said, laughing and spitting a mouthful of refried beans all over the table as he caught the plate. The second chile relleno had been saved and the late-night customers served, quickly and efficiently. Last week I wrote about the radical Sixties. This week I'm going back another decade. We're still taking about growing up in the restaurant industry, but this is Mama's story. When we lived in Southern California, Mama worked at the La Posta Mexican Restaurant for twelve years. In 1959, she was offered the opportunity of a lifetime, to go to work at the Village Inn on Lido Island where the rich and famous dined. It was expensive and exclusive. In those days, tips were expected to be ten percent of the bill. Ten percent of a ten-dollar check meant a dollar tip. (By the way, a ten-dollar check was extravagant.) At La Posta, Mama brought home hands full of dimes and quarters. When she moved to the Village Inn, she filled her pockets with dollar bills. At the Village Inn, Mama was exposed to elegant cuisine for the first time. The chef, an African-American man named Henry, was renown though out Southern California not only for the quality of his food, but for his originality and presentation. Mama and Henry became fast friends. It was Henry who taught Mama that “you eat with your eyes, not your mouth.” Mama hammered this message into our heads for the next thirty years. No one cooked a prime rib like Henry. Prime Rib was the number one attraction on the menu. Being a working-class family, subsisting primarily on Mama’s tips, we never had a prime rib in our house. However, at the end of each evening, while Mama got ready to go home, Henry packeda foil-lined bag of prime rib bones for her dog. We did not have a dog. In the morning, Papa put the ribs in a pie tin to warm them in the oven while he cooked potatoes and eggs. Then we sat around our breakfast nook and gnawed on the crispy bones, a habit I still enjoy after we have served a prime rib on our boat. As part of the high-class service, Mama learned to prepare dishes at the table-side for her guests. Caesar salads were new and elegant, Mama learned to tear the romaine, make the dressing using fresh eggs and toss the salad with a flare that delighted the diners. Desserts took the meal to a whole new level of sophistication. The Village Inn was famous for its flaming desserts. Banana’s Foster and Baked Alaska were de rigueur. Mama told us about the Volcano, which always fascinated me, although I never saw one. A Volcano was a cone-shaped mountain of ice cream with “lava flows” of hot fudge running down its slopes. At the peak of the mountain was a crater into which the waitress poured brandy, then lit the brandy to create fire and smoke on the top of the Volcano. Rich kids were delighted when Mama wheeled out the dessert cart with Volcanoes for their birthdays. In addition to the food, the show at the Village Inn included an extensive wine list. A French sommelier explained the varietals, sampled and served the expensive imported vintages offered. Mama, who knew nothing about wine, had to learn about the mystique to answer her customers’ questions. The Village Inn was the spot to see and be seen for the rich and famous. John Wayne, Humphrey Bogart and Alfred Hitchcock were among Mama’s regular customers. Like everyone else, they fell in love with Mama and asked to be seated in her section. While we were having breakfast one Sunday morning, Mama told us about a regular customer who she served the night before. He was a rich guy who always asked to sit in Mama’s section. Apparently, he made a pass at Mama that night. He showed off his money, left her elegant tips and finally asked her out on a date. He wanted to take her sailing on his yacht. The fact that she was married with a family was not obstacle to him. When I heard sailing and yacht, I was hooked. I had no idea about the adult issues at play, I just wanted to get out on the water on a sail boat. For weeks I kept asking Mama when we were going sailing with her customer. Among the rich and famous clientele of the Village Inn was Broderick Crawford. For those of you too young to remember Broderick Crawford, he was a Hollywood tough guy who won the Academy Award for best actor in the movie “All the King’s Men.” Apparently, he liked to bring that tough-guy image into his everyday life. The staff at the Village Inn hated waiting on Mr. Crawford. He swept into the lobby with his entourage like some kind of Turkish sultan, demanding the best of everything. The best table, the best food, the best service. He sat at his table and expected the waitresses to hover over him. When he wanted something, he clicked his fingers and shouted, “hey girl.” If the waitress was serving another table, he expected her to drop what she was doing and attend to his needs. None of the waitresses at the Village Inn wanted to wait on Mr. Crawford. Mama is a smart woman, she quickly learned to keep her eye on the front door. She always kept her section full, because she made it a habit to be the first one at the door to greet guests. She then graciously led them to her section and seated them. Her philosophy was that if the other waitresses wanted to keep their stations full, they would seat guests too. This worked in reverse for Broderick Crawford. Whenever Mama saw him coming through the door, she ran to greet him. She would make a big fuss over him, tell him how much she like his latest movie or that she watched his TV show last night, and seated him in someone else’s section. The rest of the staff caught on to her trick and when Mr. Crawford appeared at the door, there was a race to see who could be the first to greet him and pawn him off on one of the other waitresses. On rare occasions Mama got stuck waiting on him. On those occasions, we were sure to hear the story the next morning at breakfast. She was bitter about how hard he ran the staff, how demanding he was and how cheap he was. After exhausting her and her busboy, Mr. Crawford always left a dime tip. Ten lousy cents. Several times Mama finished her story about waiting on Mr. Crawford with the threat that she would pour a pot of coffee over his head the next time he came in. Mama was having a particularly rough night. Nothing was going right. She delivered steaks to a table, only to have them all sent back to the kitchen because they weren’t cooked to the right temperature. She slipped when making a Caesar salad and slopped dressing on Madame's fur wrap. On this particular night, things could not be gong worse. Then Mama looked to see a new party seated in her section, Broderick Crawford and guests. She was already in a huff, but this was the last straw. She approached the table and with all her will, pleasantly greeted her guests. She took their cocktail order and passed it to the bar. Within moments Mr. Crawford was snapping his fingers and shouting out, “Girl, oh girl,” across the room. Mama raced to the table only to find that his drink had not been prepared properly. She returned it to the bar and made a new one herself, just the way he liked it. Returning to the table she served his drink and waited expectantly for his approval. “That’s just perfect. Vicki, you always know how to pour a perfect martini.” Hors d’ oeuvres were served. The escargot were chewy and had to be returned. Henry was not pleased. When the steaks were delivered, Mr. Crawford took one look at his and said, “This isn’t rare. I ordered a RARE steak.” Mama returned the steak to Henry with tears in her eyes. “I’ll fix the bastard,” Henry said. He grabbed a can from the shelf. “I always keep a can of beet juice for just this occasion.” He lifted the steak off the plate, poured a little beet juice on the plate, then returned the steak. Finally, he dribbled a little beet juice over the steak. “You take this back to that cracker and let’s see if he has the nerve to send it back. You tell him that Henry prepared it himself.” “Mr. Crawford, Henry wanted me to tell you that he prepared this steak for you himself,” Mama said as she dutifully served the refurbished steak to Mr. Crawford and stood at his side to make sure it was to his liking. He cut the steak and admired the red blood oozing onto his plate. He took a bite. “Oh, this is perfect,” he said as he reached inside his jacket pocket for his wallet. Extracting a dollar bill, he handed it to Mama. “You give this to Henry and tell him that this is the best steak I’ve ever eaten. From now on, I want him to personally cook my steaks.” The ordeal wasn’t over. Mr. Crawford ran Mama ragged. Finally, they got up to leave. While the party congregated around the front door, waiting for the hat-check girl to return their coats, Mama went to clear the table. There, sitting next to Mr. Crawford’s coffee cup was a nice, shinny dime. Mama grabbed the dime and made a bee-line for the front door. “MR. CRAWFORD,” she yelled, loud enough for everyone else in the restaurant to hear. “HERE, YOU KEEP THIS. YOU PROBABLY NEED IT MORE THAT I DO,” and she shoved the dime back into his hands and closed his fingers over it. Broderick Crawford, famous Hollywood tough guy, stood and glared down at little Mama with his mouth open. He flapped his jaws a couple of times, trying to say something, then reached for his wallet. As he extracted a dollar bill, Mama turned and walked away. The Village Inn did not see Broderick Crawford for months. When he finally returned, it was with John Wayne’s party. Mr. Wayne asked for Mama’s section and Mr. Crawford sat sheepishly quiet during the entire meal. When they left, there was a crisp dollar bill next to Mr. Crawford’s coffee cup in addition to the tip the Duke left. Continuing with the theme of everything old is new again, Here's a story from the turbulent Sixties. This is another story in my continuing series about growing up in the back end of a Mexican Restaurant in Eugene, Oregon. I thought with all the social turmoil the country is going through today that this story may be appropriate. We opened El Sombrero in September of 1964. Located on the edge of the University of Oregon campus, we attracted a very intellectual crowd. Papa was the best educated man I ever met. He finished high school in Texas but, as a poor farm boy, couldn’t afford to go to college. There was no topic that didn’t interest Papa. He read everything he could get his hands on, from history to literature to poetry. He had vast amounts of Shakespeare, the Bible and poetry committed to memory. On any given day, you could count on him to quote Robert Browning, Shakespeare or John Masefield to you. Papa’s sharp intelligence and vast span of knowledge served him well with the intellectual crowd. The university professors loved to come in for lunch and debate Papa about the issues of the day or the collapse of the Roman Empire. University students found Papa a willing resource. They came in and talked to him about their assignments and he told them where to look for books and documents to research. Papa was also wildly radical in his politics. In the Thirties, he was a union organizer in San Francisco for the Longshoreman’s Union. As he worked on union activities he was exposed to the American Communist Party. Like millions of Americans during that time, he was greatly disillusioned with our system that appeared to be collapsing. The Soviet Union marketed themselves to be a “workers’ paradise” and Papa was always the champion for the working man. A couple of weeks before we opened the El Sombrero, congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution. It was an earthshaking event that went largely unnoticed in sleepy Oregon. Within a few years, the war in Viet Nam escalated. We had over half a million troops in the country and disillusionment in the war was spreading at home. Eugene and the University of Oregon were on the cutting edge of the Peace Movement. The U of O has always been a liberal school, but during the Sixties, Eugene became home to a large hippy population. It remains one of the last bastions of hippydom in the country. In high school, I was embroiled in the Viet Nam war debate. I was a lone voice expressing opposition to the war when I was a sophomore, but by the time I was a senior, I was part of a loud and growing group of students. El Sombrero became a hang out for the anti-war crowd. Every afternoon, after the lunch crowd dissipated, students, teachers and hippies gathered around tables in our restaurant plotting new demonstrations to show The Establishment that they could not continue to ignore the voice of the people. It was an exciting time and most young people on campus were involved in either pro or anti-government demonstrations. During the height of the debate, the U of O invited Huey Newton, the founder of the Black Panthers, to speak. Early one morning Papa was setting up when a group of young black men, dressed in black jeans, T-shirts, leather jackets and berets entered the restaurant. He immediately recognized Huey. Papa grabbed a couple of menus and ran out to greet them. “Good morning!” “Hey, Whitey, what you got to eat here? You got any soul food?” Huey said in a loud voice full of disdain. “No, this is a Mexican restaurant. I can fix you a great Mexican dinner.” “Hey, Whitey, you own this place? “Yes.” “So you’re exploitin’ these poor workers. Just like you exploited my people for three hundred years. Just like you made us cotton slaves.” Papa snapped. “Have you ever been a cotton slave?” he roared at Huey. “No.” “Well I have! I know what its like to hoe the cotton from sun up to sun down. I know what it’s like dragging a hundred-pound bag of cotton down row after row in the hundred-degree heat. Don’t you ever dare talk to me about being a cotton slave.” Huey backed down, ordered breakfast and quietly left. The world was in turmoil. It was 1968 and the presidential election was in full swing. Hubert Humphrey made an appearance at Hayward Field and I skipped a day of school to join the protests. Bobby Kennedy came to town. He was campaigning hard in the Oregon primary. His motorcade went down Thirteenth Avenue, in front of El Sombrero and Mama stepped outside to snap off some pictures of the historic event. A week later Bobby was dead. My world shattered when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. Mama let me skip school to watch his funeral. I couldn’t think of anything positive to live for. Eugene exploded. A group of students raided the draft board one night. All of the records were dragged from the filing cabinets and set afire in the street. A massive bon fire lit the night. Not long afterward, a protest at the University of Oregon chapter of the ROTC turned violent. Police were called in and a full-scale riot ensued. The students managed to set the ROTC building on fire and burned it to the ground.

A massive candle-light parade was planned. Students and protestors from all over the West Coast and the country came to Eugene to participate. Tens of thousands of people filled the streets carrying banners and placards. Young girls wore tie-dyed dresses, and flowers and feathers in their hair. The young men sported beards and long hair. In the front window of El Sombrero was a large psychedelic poster announcing the upcoming protest. As was his want, Papa was in the thick of the planning. In the afternoons and late at night, the protest planners sat in our restaurant and plotted mischief over cups of coffee and plates of tacos. The march started at the University and wound down Thirteenth Avenue to downtown Eugene where speakers further incited the crowds. Nervous city fathers decided not to issue a parade permit. The lack of a permit didn’t slow the protest organizers a bit. The march went on. Mama and Papa closed the restaurant that night to support the protest. They attended the rally on campus, but eschewed the march, they had to get up the next morning to open the restaurant. I walked the route with my candle in hand. The Eugene police department was woefully understaffed to handle demonstrations on this scale. They made a presence, but were overwhelmed by the sheer size of the crowd. They stood helplessly by while the march began. Within a few blocks the march turned ugly. Radical leaders incited the crowd. Big business was a target of their anger. First someone wailed about the evils of the military-industrial complex. Then we heard about how The Establishment was destroying our freedoms. There was construction going on down the street and the site had stacks of bricks in front of it. This was unfortunate timing. Someone picked up a brick and hurled it through the window of the US Bank branch across the street from El Sombrero. The anger of the crowd exploded. Soon bricks were flying through the air. The police moved in, but were overpowered by the crowd. The march moved down the street shattering windows, pulling displays down and generally making mayhem in the streets. By all standards, the protestors thought that the march was a great success. It ended in front of the Federal Courthouse in downtown Eugene. Speakers with megaphones harangued the crowd late into the night. The sweet smell of pot filled the air. As the wee hours of the morning approached the crowd began to dissipate. Some of the mob slipped off to grab a few winks at their crash pads or their old lady’s house. Some just found grassy spots along the downtown sidewalks on which to collapse. The sun rose to reveal the extent of the chaos. Merchants and office workers returned to claim downtown, but there was a trail of damage where the march had passed. Hardly a business was unaffected. Windows had been smashed, storefronts looted, banks and insurance offices fouled. When Papa arrived at El Sombrero to begin his set up for the day, the street was in ruins. It looked like downtown Berlin in 1945. The pavement was littered with broken glass, articles of clothing dragged from display windows, books from the nearby bookstore, goods from the little drug store down the street. There was no rhyme or reason to the destruction, the protesters were just expressing their helplessness and anger. El Sombrero survived the night without a scratch. As the march wound past our restaurant, a group Black Panthers formed a human shield in front of our establishment. “Hey, man, they’re cool,” they told the angry protesters as they approached, bricks and rocks in hand. In spite of the anger and destruction of that night, we remained unscathed. |

AuthorPendelton C. Wallace is the best selling author of the Ted Higuera Series and the Catrina Flaherty Mysteries. Archives

December 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed